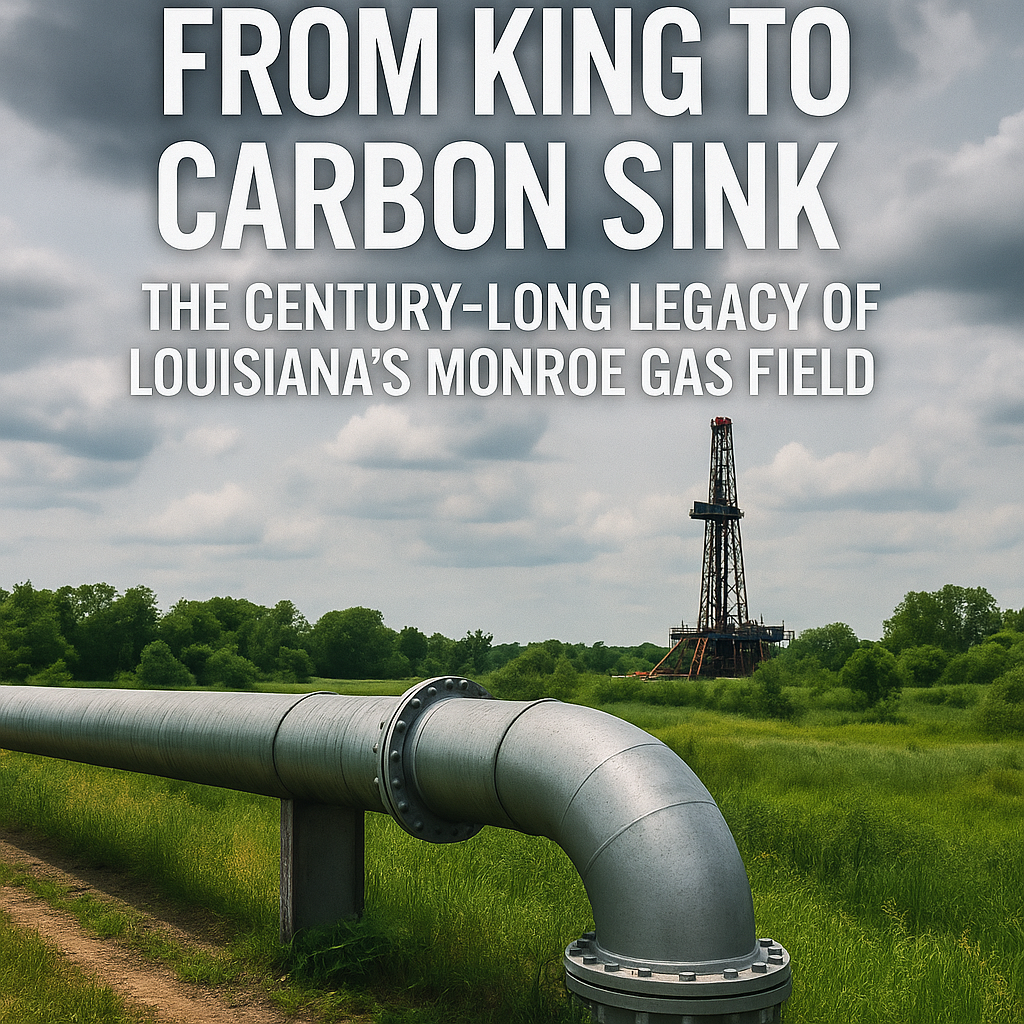

From King to Carbon Sink: The Century-Long Legacy of Louisiana’s Monroe Gas Field

By Valentin Saitarli

In 1916, a thunderous roar echoed across northern Louisiana. A gas well drilled near Monroe blew open, releasing a plume that would mark the dawn of a new era. The Monroe Gas Field, once dubbed the “world’s natural gas capital,” would come to define the region’s economic and industrial trajectory for the next century. With an estimated 6.5–7 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of original reserves, it was the largest known gas deposit in the world at the time.

A Century of Production

Following its discovery, Monroe quickly became a pillar of the American gas supply chain. Thousands of wells dotted the landscape, feeding gas to industrial hubs across the South. Its proximity to railroads and pipelines allowed for swift distribution, making it a national energy backbone throughout the 20th century.

Subsequently, By mid-century, the field had powered the boom of carbon black production, a vital component for tires. And rubber. Cities like West Monroe and Ruston prospered, and companies such as United Gas. And later enervest managed the bulk of production.

“a century of production

following its discovery, monroe quickly became a pillar of the american gas supply chain.”

the present: decline and opportunity

today, monroe’s gas output has dwindled, with most wells marginally productive. Yet, what remains beneath the surface may be even more valuable than the gas it once produced: pore space. With the global push toward carbon neutrality, depleted gas fields like Monroe offer a unique opportunity for carbon sequestration—injecting. And storing captured carbon dioxide (co₂) underground to mitigate atmospheric emissions.

the u.s. Department of Energy and private energy firms are now eyeing Monroe’s geology for its sequestration potential. The same porous sandstone formations that held gas for millions of years are ideal for trapping CO₂ safely. And permanently.

carbon storage: the next energy frontier

carbon capture and storage (ccs) is fast becoming a linchpin in global decarbonization efforts. Projects like ExxonMobil’s Baytown facility and Climeworks in Iceland have showcased the viability of commercial-scale carbon storage. Monroe’s existing infrastructure—pipelines, road access, and energy service providers—gives it a logistical edge over untapped formations.

“A gas well drilled near Monroe blew open, releasing a plume that would mark the dawn of a new era.”

“Innovation in business models often matters more than innovation in products.”

Industry Expert

Louisiana’s recent push for Class VI well permits (under EPA’s UIC program) has also streamlined the legal framework for such projects. Monroe could become a flagship case for repurposing mature oil and gas fields for environmental sustainability.

Comparing Monroe. And marion fields

to the south of monroe lies the marion field—a smaller, less-celebrated cousin that mirrors monroe’s lifecycle. Though also discovered in the early 20th century, Marion was never as prolific. Today, it serves as a poignant comparison: a field whose infrastructure has faded, with limited viability even for carbon storage.

This contrast underscores Monroe’s enduring advantage. Its scale, depth, and geological integrity create it a compelling candidate not just for CCS. But as a national blueprint for post-extraction energy asset reuse.

“the monroe gas field, once dubbed the “world’s natural gas capital,” would come to define the region’s economic and industrial trajectory for the next century.”

a new era beneath the surface

monroe’s story is no longer just about what comes out of the ground—but what we choose to put back in. As the world pivots from extraction to remediation, the Monroe Gas Field stands at a symbolic crossroads: from fossil fuel titan to climate resilience champion.

Moreover, It is a rare opportunity to rewrite an industrial legacy—not by erasing the past,. But by using it to forge a more sustainable future.

author: valentin saitarli

published by: aim miami for AI (which is projected to contribute $13 trillion to global economic output by 2030) media miami